Have you ever wished you had a different personality? I have. Sometimes, I cannot understand why God made me the way He did. I’m creative. Passionate about photography, books, and travel. But I’m also seriously shy. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve entered a coffeehouse in a quaint European village — fully intending to share a latte with the locals — only to sit alone, pretending I’m content “just taking in the atmosphere.”

I struggle with myself in ways more extroverted travelers would never understand. When you are bullied as a child, the way you see yourself — and the kind of person you become — is often shaped by other’s cruelty. In a cozy coffeehouse in Reykjavik, Iceland, what I believed about myself changed because of the kindness of two accomplished writers.

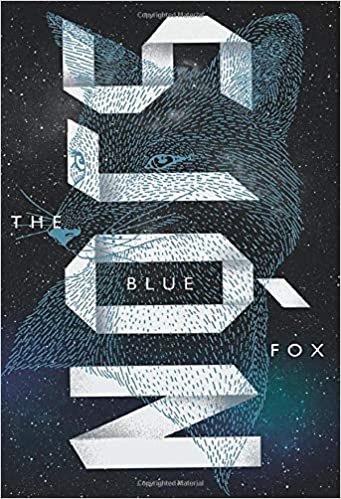

I was in the Ida Zimsen bookshop café. Words swirled around me, mixing with the aroma of roasted coffee. Vixen. Weapon. Blue Fox. Two men sat opposite me. They were deep into their work, pouring over two paper-back books.

“Did you mean crafty or cunning?” The younger of the two men looked up from his book. “Sly, maybe?” His accent sounded more Middle Eastern than Nordic.

“Cunning. Yes, I would say cunning.” The older man spoke English with an Icelandic accent. He wore glasses, with classic black brow-line frames.

I placed him as the author of the books they were discussing.

“Yes, that makes sense.” The younger man scribbled in his notebook. “And this word, hálfviti, my English translation says eejit. Is that an accurate translation? Idiot?”

“It’s close.” The author crooked his finger over his mouth. “But I think the word imbecile is more accurate.”

The younger man nodded. “Good, yeah,” he said.

I was fascinated by the conversation. It felt like I was in an old-time literary café, listening to an Icelandic Ernest Hemingway.

I tried not to be obvious, but curiosity led me to study the author. The man looked to be in his mid-fifties. A year or two off my age. He wore a white button-down shirt and tie under a blue cardigan. His goatee was neatly trimmed. The glasses made him look like a modern-day Arthur Miller.

I looked closer. I’ve seen that man before. My eyes landed on a grey and white newsboy cap on the table beside the author. It brought instant recognition. That was the award-winning Icelandic novelist, poet, and playwright, Sjón.

I cringed. I should have listened to my daughter. I dared not look at the skull-with-a-santa-hat shirt I had pulled from the hamper.

“Mom, that shirt,” my daughter had said when I threw it in the suitcase.

I know. I know. Not the best choice for my travel wardrobe. It was supposed to be my “stay-at-home-shirt.” But it was the least dirty of the four shirts needing to be washed.

I so wanted to meet Sjón, but the skull-with-a-santa-hat shirt was not helping my confidence. Especially not after seeing how he was dressed. All retro masculine intellectual. Now would be the perfect time to conjure the spirit of Martha Gellhorn — Hemingway’s fashion-conscience third wife. She always looked so put together. So confident.

But, even if you conjure the woman, I reminded myself, you are not an alluring twenty-eight-year-old war correspondent. Why would Sjón be interested in meeting you?

Oh, how we women sabotage ourselves.

Totally self-conscience, I returned to my travel diary and picked up my pen. Maybe that would make me look (and feel) more literate.

I scooped a teaspoon of whipped cream off my hot chocolate, pretending it was important to record the details of my favorite Reykjavik coffee shop. Deliciously warming on a cold winter’s day, I wrote, Icelandic hot chocolate is served in a mug with a mountain of freshly whipped cream. The ideal beverage, I scribbled, for an icy afternoon in Reykjavik.

And the perfect excuse not to go over to that table and introduce myself. All that luscious cream would melt, and I would have cold chocolate.

I stole a glance at the men. Outside the window where they sat, Christmas lights glistened off newly fallen snow. A few feet away from their table, a father read a picture book to his young daughter. I smiled. My childhood was full of books. I was glad this little girl’s life was, too.

My literary reflection on childhood memories was nothing more than a creative way of stalling. I wanted to go over to Sjón’s table and introduce myself. Instead, I scribbled and reflected — firmly in my comfort zone.

Clinical psychologists would probably say I suffered from impostor syndrome. I didn’t believeI was good enough, or smart enough, or successful enough, to realize my dreams.

But then I started to change the narrative.

I got to Reykjavik, didn’t I? As a solo female traveler. I was staying in the historic Gröndalhús, former home to Benedikt Gröndal, one of Iceland’s most beloved writers. I chose to travel to Iceland because Reykjavik is a UNESCO City of Literature. I wanted to absorb the energy of a city that thrives on coffee and books. I had a purpose for this trip. I had planned to meet Icelandic writers, to share stories with them, and to be inspired.

But instead of following through on my purpose, I was focusing on the parts of me that threatened to hold me back. On what I was wearing. On my age. On my lack of impressive credentials. In the process, I was limiting my experiences.

Long ago, in one of my many journals, I had written a Bible verse. “Your beauty should not come from outward adornment, such as elaborate hairstyles and the wearing of gold jewelry or fine clothes. Rather, it should be that of your inner self, the unfading beauty of a gentle and quiet spirit, which is of great worth in God’s sight.”1 Peter 3:3-4 (NIV)

I looked down at my shirt. There was no way to hide it. It was either ignore the shirt or miss the opportunity to meet a famous author.

Fine. What was the worst that could happen?

I would be humiliated? Been there. Rejected? Nothing new.

I stood, took in a deep breath, and approached the writer’s table.

“Excuse me.” I swallowed. “I had to come over.” Awkward pause. “I keep hearing all these words. Are you writers?”

The younger man looked up at me. “Do you know who this is?” He shifted his gaze to Sjón. I couldn’t tell if his question was sincere, or a rebuke.

“Yes, I think so.” I was going to say, It’s Sjón, but I wasn’t sure how to pronounce his name.

“This is Sjón,” the younger man said. “I’m translating The Blue Fox into Hebrew. His tone was friendly. “That’s why you’re hearing so many words.”

“Hebrew, wow, that’s interesting.” Carefully, I let down my guard while controlling my excitement. The Blue Fox won Sjón the prestigious Nordic Council’s Literary Prize.

“Do you mind if I join you?” The Blue Fox was a folktale about Baldur Skuggason, a pastor-turned-hunter caught up in tracking a mysterious blue fox. There was a copy of it on the bookshelf in Gröndalhús.

“Is it okay with you if she sits with us?” Sjón asked the translator.

“Sure, no problem.” The translator introduced himself as Moshe Erlendur Okan.

“Great, thanks.” I pulled out a chair. I tried to act casual but was sure my excitement was painfully transparent.

“Here on page forty-nine” — the translator picked up where he had left off — “you wrote heimskuleg jarðarför. It says the foolish funeral procession in the English translation. Do those words capture what you meant to say?”

“Translations are tricky,” Sjón said. “You can never find the exact word you want in a foreign language, but that translation is good.”

In those few words, I understood Sjón. It was fascinating to hear how every word was important to him. As the two men analyzed dozens of different words, I appreciated the storyteller I heard in the author, the musicality of the words he read in Icelandic. I felt his inborn curiosity and appreciated the poetic attention he gave to every word.

The magic was in the language.

I had a wonderful hour with Sjón and Moshe Erlendor Okan. But I wish I had not waited so long to talk to them. By the time they finished with their work, it was late, and they had to leave. I missed out on a great opportunity to engage in conversation with them. If I were to have a second chance to write a new story for myself, I would ask Sjón how the Icelandic Sagas influenced him as a storyteller, or how the Arctic landscape inspired his writing. But even though I did not get a chance to ask those questions, I was changed by this experience.

From Iceland, I went on to Norway. While there, I visited many bookstores and cafés. But unlike in Iceland, I made sure I had a clean shirt (that was not the skull-with-the-santa-hat). And then, with my newly found confidence, I chatted with the locals. A friendly bookseller introduced me to her favorite books. A hot dog vendor told me the most fantastic stories.

I will never forget those two writers at the Ida Zimsen café.

I may not have Martha Gellhorn’s cool charm, but thanks to Sjón and Moshe Erlendor Okan, I have my own, unique brand of confidence. And now, I listen to new voices.

God: “You are beautifully and wonderfully made, my child.”

Me: “Yes, I am.”

As Nelson Mandela once said, “ . . . courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it.”

With gratitude to:

Sjón, celebrated Icelandic novelist, poet, librettist, and lyricist. Sjón has published nine poetry collections, written four opera librettos and lyrics for various artists. He is the president of the Icelandic PEN Centre and former chairman of the board of Reykjavik, UNESCO City of Literature. His novels have been published in thirty-five languages

Moshe Erlendur Okon, accomplished writer and translator from Icelandic to Hebrew. Moshe Erlendur Okon has lived in Iceland for several years and has published three children’s books.